"In 1935, quite by accident, I came across an unusual stone in the River Boite.

I put it in a cupboard and asked everyone what type of stone it might be.

An English botanist told me it could only be a piece of fossilised coral.

This made me all the more curious.

For months, I moved from one valley to another to find the place where the coral could have come from.

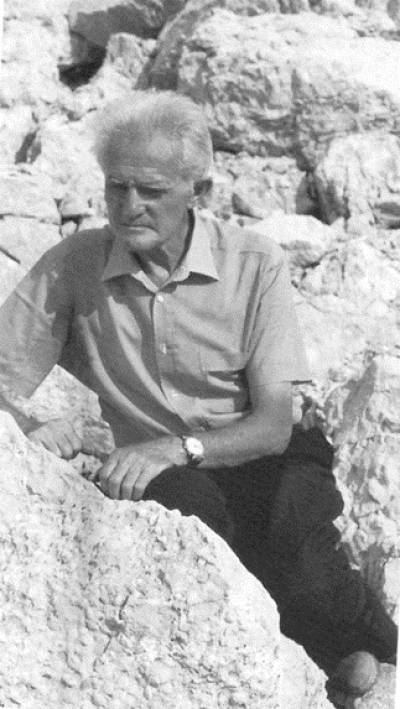

One autumn day, I sat down at the foot of the Faloria to rest.

When I looked on the ground, I found myself surrounded by lamellibranchia, ammonites and many other fossilised organisms.

It was like being on a sea shore. All the fossils were in good condition as if someone had protected them.

Corals and sponges seemed to have just appeared out of a tropical sea...."

Without knowing chemistry, he noticed that the humus acids gradually destroy the compact limestone casing of the fossils while not damaging the latter in any way, especially corals, sponges and molluscs.

Rare and beautiful pieces remain hidden and then gradually emerge in all their splendour. Zardini prompted researchers throughout the world to once more address the problem of "cassian" species, thanks to the great variety of specimens in his collection.

Important Universities began studying his fossils. Little by little, through publications and with the cooperation of well-known international experts, he began to make his work known: lamellibranchs, cephalopods, gasteropods, sponges, cephalopods, gasteropods, sponges, echinoderms and bivalves appear to have no secrets for him.

His scientific contribution was so great that he was appointed affiliate researcher at the Smithsonian Institute in Washinton. The Faculty of Natural Sciences of Modena University presented him with an honoris causa degree in Natural Sciences, saying that: "Zardini has far surpassed the threshold that divides the collector from the scientist"

He was totally dedicated to the mountains and what these hold in custody. He lived his dream to the full, like a boy, and so he stayed until the day he died: 16 February 1988.

Without knowing chemistry, he noticed that the humus acids gradually destroy the compact limestone casing of the fossils while not damaging the latter in any way, especially corals, sponges and molluscs.

Rare and beautiful pieces remain hidden and then gradually emerge in all their splendour. Zardini prompted researchers throughout the world to once more address the problem of "cassian" species, thanks to the great variety of specimens in his collection.

Important Universities began studying his fossils. Little by little, through publications and with the cooperation of well-known international experts, he began to make his work known: lamellibranchs, cephalopods, gasteropods, sponges, cephalopods, gasteropods, sponges, echinoderms and bivalves appear to have no secrets for him.

His scientific contribution was so great that he was appointed affiliate researcher at the Smithsonian Institute in Washinton. The Faculty of Natural Sciences of Modena University presented him with an honoris causa degree in Natural Sciences, saying that: "Zardini has far surpassed the threshold that divides the collector from the scientist"

He was totally dedicated to the mountains and what these hold in custody. He lived his dream to the full, like a boy, and so he stayed until the day he died: 16 February 1988.